What can wine learn from paths, penguins, chickens?

Do you go your way, or the easy way? Too many people insist on their way.

This is post is free to read. Mostly. Everyone gets the story. But paid subscribers get the insights you need to turn it into action. I think that’s fair for this one. Do please become a subscriber - you’ll find this invaluable if you make, sell, market, or study wine. If you’re doing the WSET Diploma or MW you’ll wonder why you didn’t before.

The thing above is called a “desire path”. For international readers, the murky thing around it is called “Great Britain”. And it looks like that much of the time. Keep this in mind the next time you find someone from Britain who’s a bit glum. They probably just walked the dog.

Anyway, a desire path is informal trail created when people walk the way they want, not the way they’re meant to go. And it’s always the easier way. A desire path tells us a lot about wine and how people buy it. I’ll let you into a secret too. I use the lessons it tells us in my own work. Although they don’t involve a chicken, but they do involve a penguin.

“Chicken Wine” is a desire path

I am indebted to my friend and top wine substacker Henry Jeffreys who recently wrote about animal wine labels. And specifically “chicken wine”.

By “Chicken Wine” we mean La Vieille Ferme - the hugely successful and popular brand from the Perrin Family in France. It’s called the chicken wine because it has two chickens on the label. And that - it turns out - is a brilliant thing. As Henry points out, it “has become something of a cult these days so much so that the producer has even rebranded it after its nickname.”

Chicken wine now has its own #hashtag and memes. So they must be serious.

Of course this rebrand has been presented as an act of genius on the part of the Perrin family. I’m not saying they’re not clever. They are. After all, they got into bed (metaphorically) with Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie to make Miraval Rosé. After which Angelina got out of the bed and sold her side - pillows and duvet included - to Stolichnaya. Much to Brad’s discombobulation. But not the Perrins who made a Champagne with Brad and Rudolphe Peters (Perrin, Pitt, Peters…). They’re doing very well thank you.

But that’s by-the-by. The embrace of “chicken wine” is not so much an act of genius by the Famille Perrin as bowing to the inevitable. It is - I argue - a mental “desire path”.

It’s sometimes said that humans are “cognitively lazy”. They’re not. At least not according to most psychologists. But our brains are efficient. Much as we look for the most efficient ways to walk through dank parks, we look for the most efficient way to think about things. Which means we don’t always think about things the way people would like us to. Like their brand names.

“La Vieille Ferme” is French. And that’s a problem for starters. I’m not totally stupid. But I failed French O level (a sort of prehistoric qualification once taken by 16 year olds) an unprecedented five times. Dr Ritchie - brilliant French teacher that she was - could make me stay back for an extra hour of tuition as much as she wanted. I still wouldn’t remember what “La Vieille Ferme” was once Major Cobb called silence in the exam hall and said for the sixth time “you can turn your papers over… now”.

But “the chicken wine”? That’s another story. I can remember that, and picture it, and find it funny, and engaging even after drinking a bottle of the stuff.

So "the chicken wine” becomes a sort of mental desire path. It’s the name we’d have given La Vieille Ferme if we’d been asked.

Animal Magic

This is a lesson the wine trade have been told for a long time. But only listened to relatively recently.

The rise of “Critter Labels” is usually seen as a phenomenon of the 90’s and 00’s. Yellow Tail is perhaps the most famous. But there’s Fat Bastard Chardonnay with a hippo on it, Goats do Roam (a goat), Chat on Oeuf (a cat), and a surprisingly large number of quite smart wines featuring dachshunds.

But animal labels are far from a new phenomenon. Guy Woodward recently shared this historic wine list from “posh people’s department store” Harrod’s:

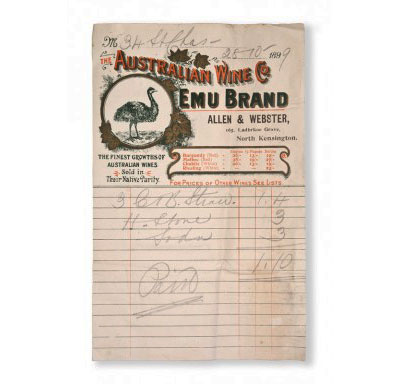

Look top right and you’ll see of Kangaroo Burgundy and Port. There’s also Emu brand Chardonnay and Riesling. In fact Emu Brand was one of the very first “critter brands” registered as a trademark in 1883 by manager James Cocks. Here’s an invoice from 1899:

And there’s a brand called “Oomoo”. A few years ago Hardy’s, who owned the brand, revived the labels. I think they’re rather attractive

Those Australians were tapping into something that we understand better today. Animals are generally easier to remember and recall in logos. Mostly because of an animal’s innate ability to capture our attention and evoke emotional and cultural associations in our minds. Also psychologists have found that animals possess characteristics that humans often find relatable, memorable, and engaging. And they make us think of things like strength, loyalty, or playfulness. We even end up forming emotional bonds (as we will see below the paywall, this is critical). Think of Sergei the meerkat, Tony the tiger, The Honey Monster… every one of those animal brands enhances brand recall and fosters loyalty.

Simple, but not too simple

One of the businesses I work with is a growing wine recommendation platform in Sweden called Pinvino. The penguin above is our logo. You’re thinking - what does a penguin have to do with wine? And that’s part of the point. Nothing. Penguins live on the only continent in the world with no vines. But it does mean that we already stand out in a market littered with logos of barrels, bunches of grapes, and stylised bottles. A useful benefit known as the Von Restorff Effect.

But also… people like penguins. Why not have a logo of something people like, and find easy to remember. Rather than worry about it being "relevant”. Chickens don’t make wine. But it’s easier to remember “the chicken wine” because there’s a chicken on the bottle. Penguins aren’t known for their wine recommendations. But they’re easy to remember too. And funny.

And then there’s the name. “Pingvin” is the Swedish word for Penguin1. So there’s a bit of wordplay there. And when you figure out the wordplay, you feel pleased with yourself for making the connection. It evokes an emotion (vital, as paid subscribers will see). Appropriately - for a Swedish brand - this is known as the IKEA Effect. Your brain helped make that little joke, so you feel more warmly towards it. Just like the slightly shonky table in your living room.

The logo itself (by the brilliant Simon Sved) is another example of this effect of making something easy to like and remember, but building in a hidden layer that makes it even more memorable.

Here’s the penguin. And if you look closely you’ll see s/he’s2 holding a bottle. It’s an example of “negative space” design. Like the famous arrow that’s hidden between the e and x of FedEx

Once you see it, you can’t ignore it. And from then on it occupies - in Sir John Hegarty’s famous phrase - “the most expensive piece of real estate in the world. The corner of someone’s mind”.

Wine makers (and marketers) are often too literal. Too rational. Too logical. “It comes from this chateau… we’d better have a picture of that chateau on it”. Or “it’s French, the name should be French”. Or “we help people buy bottles of wine, so our logo should be bottles and we should call ourselves “winebuyerexpert.com”. All of these make a kind of sense. But they mean people have to think about your wine and your brand the way you want them too. On a slightly convoluted path that winds unnecessarily around some foggy park.

They just want to get to the wine. Make it easy for them.

But not too easy.

For paid subscribers, there’s advice on how to apply this below…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Joe Fattorini's Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.